Skewes' number

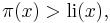

In number theory, Skewes' number is any of several extremely large numbers used by the South African mathematician Stanley Skewes as upper bounds for the smallest natural number x for which

where π is the prime-counting function and li is the logarithmic integral function. These bounds have since been improved by others: there is a crossing near  . It is not known whether it is the smallest.

. It is not known whether it is the smallest.

Contents |

Skewes' numbers

John Edensor Littlewood, Skewes' teacher, proved (in (Littlewood 1914)) that there is such a number (and so, a first such number); and indeed found that the sign of the difference π(x) − li(x) changes infinitely often. All numerical evidence then available seemed to suggest that π(x) is always less than li(x), though mathematicians familiar with Riemann's work on the Riemann zeta function would probably have realized that occasional exceptions were likely by the argument given below (and the claim sometimes made that Littlewood's result was a big surprise to experts seems doubtful). Littlewood's proof did not, however, exhibit a concrete such number x.

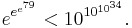

Skewes (1933) proved that, assuming that the Riemann hypothesis is true, there exists a number x violating π(x) < li(x) below

In (Skewes 1955), without assuming the Riemann hypothesis, Skewes managed to prove that there must exist a value of x below

Skewes' task was to make Littlewood's existence proof effective: exhibiting some concrete upper bound for the first sign change. According to George Kreisel, this was at the time not considered obvious even in principle. The approach called unwinding in proof theory looks directly at proofs and their structure to produce bounds. The other way, more often seen in practice in number theory, changes proof structure enough so that absolute constants can be made more explicit.

Although both Skewes' numbers are big compared to most numbers encountered in mathematical proofs, neither is anywhere near as big as Graham's number.

More recent estimates

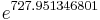

These (enormous) upper bounds have since been reduced considerably by using large scale computer calculations of zeros of the Riemann zeta function. The first estimate for the actual value of a crossover point was given by Lehman (1966), who showed that somewhere between 1.53×101,165 and 1.65×101,165 there are more than 10500 consecutive integers x with π(x) > li(x). Without assuming the Riemann hypothesis, H. J. J. te Riele (1987) proved an upper bound of 7×10370. A better estimation was 1.39822×10316 discovered by Bays & Hudson (2000), who showed there are at least 10153 consecutive integers somewhere near this value where π(x) > li(x), and suggested that there are probably at least 10311. Chao & Plymen (2010) gave a small improvement and correction to the result of Bays and Hudson. Bays and Hudson found a few much smaller values of x where π(x) gets close to li(x); the possibility that there are crossover points near these values does not seem to have been definitely ruled out yet, though computer calculations suggest they are unlikely to exist. (Saouter & Demichel 2010) find a smaller interval for a crossing, which was slightly improved by (Zegowitz 2010). The same source shows that there exists a number x violating π(x) < li(x) below  . The number could be reduced to 727.951338611, assuming Riemann hypothesis.

. The number could be reduced to 727.951338611, assuming Riemann hypothesis.

Rigorously, Rosser & Schoenfeld (1962) proved that there are no crossover points below x = 108, and this lower bound was subsequently improved by Brent (1975) to 8×1010, and by Kotnik (2008) to 1014.

There is no explicit value x known for certain to have the property π(x) > li(x), though computer calculations suggest some explicit numbers that are quite likely to satisfy this.

Wintner (1941) showed that the proportion of integers for which π(x)>li(x) is positive, and Rubinstein & Sarnak (1994) showed that this proportion is about .00000026, which is surprisingly large given how far one has to go to find the first example.

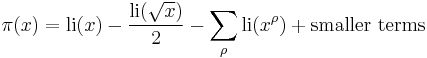

Riemann's formula

Riemann gave an explicit formula for π(x), whose leading terms are (ignoring some subtle convergence questions)

where the sum is over zeros ρ of the Riemann zeta function. The largest error term in the approximation π(x) = li(x) (if the Riemann hypothesis is true) is li(√x)/2, showing that li(x) is usually larger than π(x). The other terms above are somewhat smaller, and moreover tend to have different complex arguments so mostly cancel out. Occasionally however, many of the larger ones might happen to have roughly the same complex argument, in which case they will reinforce each other instead of cancelling and will overwhelm the term li(√x)/2. The reason why the Skewes number is so large is that these smaller terms are quite a lot smaller than the leading error term, mainly because the first complex zero of the zeta function has quite a large imaginary part, so a large number (several hundred) of them need to have roughly the same argument in order to overwhelm the dominant term. The chance of N random complex numbers having roughly the same argument is about 1 in 2N. This explains why π(x) is sometimes larger than li(x), and also why it is rare for this to happen. It also shows why finding places where this happens depends on large scale calculations of millions of high precision zeros of the Riemann zeta function. The argument above is not a proof, as it assumes the zeros of the Riemann zeta function are random which is not true. Roughly speaking, Littlewood's proof consists of Dirichlet's approximation theorem to show that sometimes many terms have about the same argument.

In the event that the Riemann hypothesis is false, the argument is much simpler, essentially because the terms li(xρ) for zeros violating the Riemann hypothesis (with real part greater than 1/2) are eventually larger than li(x1/2).

The reason for the term  is that, roughly speaking,

is that, roughly speaking,  counts not primes, but powers of primes

counts not primes, but powers of primes  weighted by

weighted by  , and

, and  is a sort of correction term coming from squares of primes.

is a sort of correction term coming from squares of primes.

References

- Bays, C.; Hudson, R. H. (2000), "A new bound for the smallest x with π(x) > li(x)", Mathematics of Computation 69 (231): 1285–1296, MR1752093, http://www.ams.org/mcom/2000-69-231/S0025-5718-99-01104-7/S0025-5718-99-01104-7.pdf

- Brent, R. P. (1975), "Irregularities in the distribution of primes and twin primes", Mathematics of Computation 29 (129): 43–56, doi:10.2307/2005460, JSTOR 2005460, MR0369287

- Chao, Kuok Fai; Plymen, Roger (2005), "A new bound for the smallest x with π(x) > li(x)", International Journal of Number Theory 6 (03): 681–690, arXiv:math/0509312, doi:10.1142/S1793042110003125, MR2652902

- Kotnik, T. (2008), "The prime-counting function and its analytic approximations", Advances in Computational Mathematics 29 (1): 55–70, doi:10.1007/s10444-007-9039-2

- Lehman, R. Sherman (1966), "On the difference π(x) − li(x)", Acta Arithmetica 11: 397–410, MR0202686

- Littlewood, J. E. (1914), "Sur la distribution des nombres premiers", Comptes Rendus 158: 1869–1872

- Skewes, S. (1933), "On the difference π(x) − Li(x)", Journal of the London Mathematical Society 8: 277–283

- Skewes, S. (1955), "On the difference π(x) − Li(x) (II)", Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 5: 48–70, MR0067145

- te Riele, H. J. J. (1987), "On the sign of the difference π(x) − Li(x)", Mathematics of Computation 48 (177): 323–328, JSTOR 2007893, MR0866118

- Rosser, J. B.; Schoenfeld, L. (1962), "Approximate formulas for some functions of prime numbers", Illinois Journal of Mathematics 6: 64–94, MR0137689

- Saouter, Yannick; Demichel, Patrick (2010), "A sharp region where π(x) − li(x) is positive", Mathematics of Computation 79 (272): 2395–2405, doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-10-02351-3, MR2684372

- Zegowitz, Stefanie (2010), On the positive region of

, pp. 69 pp., http://eprints.ma.man.ac.uk/1547/

, pp. 69 pp., http://eprints.ma.man.ac.uk/1547/ - Rubinstein, M.; Sarnak, P. (1994), "Chebyshev's bias", Experimental Mathematics 3 (3): 173–197, MR1329368, http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.em/1048515870

- Wintner, A. (1941), "On the distribution function of the remainder term of the prime number theorem", American Journal of Mathematics (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 63 (2): 233–248, doi:10.2307/2371519, JSTOR 2371519, MR0004255

External links

- Patrick Demichel. The prime counting function and related subjects. http://web.archive.org/web/20060908033007/http://demichel.net/patrick/li_crossover_pi.pdf retrieved 2009-09-29

|

|||||||||||||||||||